The small British Overseas Territory of Montserrat has had some tumultuous times. In July 1995, the Soufrière Hills volcano erupted, covering the former capital of Plymouth in volcanic mud and rendering the southern half of the island uninhabitable. 90 percent of its 13,000 population evacuated or emigrated out, and the population has only recently rebounded to close to 5,000 in recent years.

I was then mighty surprised, when I was looking at the data for the island, that the Human Development Index, or HDI, was unavailable for the island. Perhaps it's its status as a territory, or due to insufficient data, that there's no mention on it on the United Nations Development Programme's 2019 Human Development Report. The most recent World Bank document I could find from the island is from 1985. The United Nations Statistics Division has better data, but it's more than a decade old, often incomplete, and sometimes just plain wrong.

|

| As much as I love UNdata, I highly doubt Montserrat is entirely female. |

Given the lack of information (and sometimes data), I decided to set sights on obtaining the HDI of Montserrat, whatever it takes.

First, I must clarify what the HDI is: a statistic composite of life expectancy, education, and per-capita income. The closer it is to 1, the higher the human development of the territory in question. As of 2020, Eastern Caribbean countries are in the 0.700-0.799 tier, listing them as "high" HDI nations.

The math behind it seems complicated at first, but if you have the data, it's almost trivial to compute.

| LEI = 0.8508 |

The first data point needed is the Life Expectancy Index, which can be calculated from the Life Expectancy at Birth. This data is readily available at the CIA World Factbook page.

|

| EI = 0.6246 |

The second data point needed is the Education Index. This is significantly harder, as I could not find any data on the mean years of schooling or the expected years of schooling. I started with the six years of compulsory primary education and assumed full enrollment. The Government of Montserrat has a statistics department, but I had no luck accessing the education data. I resorted to use a 2014 Statistical Digest of the Ministry of Education, which had enough data to at least try to work it out. From there, I found out Montserrat had a drop-out rate of 2% between primary and secondary education so about 98% of students finish secondary education, giving a combined 10.90 expected years of schooling.

What about tertiary education? Montserrat possesses a community college, a branch of the public University of the West Indies, and the private University of Science, Arts and Technology. I could only find graduation info for the community college, for the class of 2017. I hope they are doing well.

In 2017, there were a total of 69 students in attendance. Assuming a constant rate of intakes and graduates over a two-year period, there was an intake of 34.5 students per year. This represents 65% of all secondary education graduates and, assuming that they all come from high school, this raises the expected years of schooling to 12.20.

|

| It's just a guesstimate, but it seems reasonable. |

For the mean years of schooling, I would need historical or more complete demographic data of the population, which I fear I will be unable to obtain. So I used an estimation taking the mean years of schooling for six similar Caribbean nations: Saint Kitts and Nevis, Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Dominica, taken from the UNDP's 2019 report. The arithmetic mean of them equals 8.5785 years, and that seemed reasonable enough to use for Montserrat.

|

| II = 0.7299 |

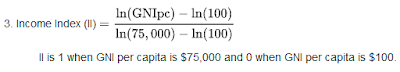

With that data, the Education Index could be calculated, and we are left with the Income Index. For this, the UN Statistics Division did have good data which I promptly used.

| HDI = 0.7293 |

Last, but not least, the calculation of the HDI requires to obtain the geometric mean of all three of them to obtain a final result.

And with that, the final estimate for Montserrat's HDI equals... 0.7293. This figure is on the lower end of the Caribbean countries, but still well within the range, and on the "high" HDI tier.

While I doubt I am the first person in the world to calculate Montserrat's HDI, I cannot find any other attempt at calculating it in my academic research. This method leaves more than a couple of things to be desired in terms of data and methodological accuracy but, for a preliminary analysis of its HDI, it works just fine. Further research is needed, however, for a better and more precise understanding of the socio-economic situation of Montserrat.

.svg/500px-Doomsday_clock_(1.67_minutes).svg.png)